ZULU ROCK LINER NOTES by Vivien Goldman

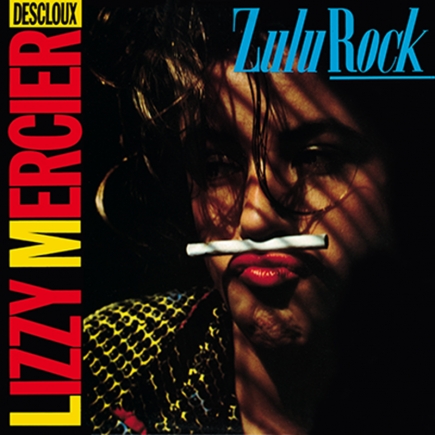

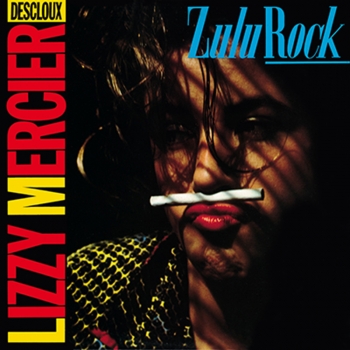

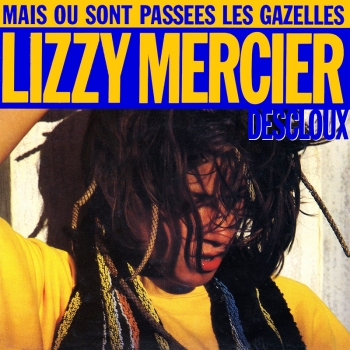

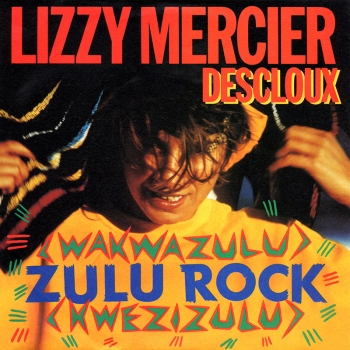

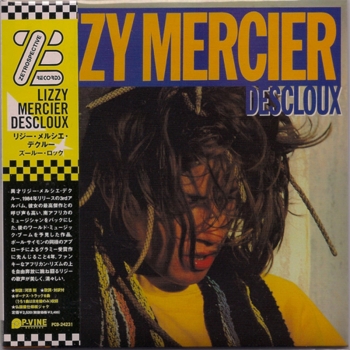

In the ongoing sonic adventures of Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, the stylish rogue poet, artist and singer-songwriter continued to be, as the French say, “dans le vent.” The expression means hip, cool; literally, in the wind. Still, her third album, “Zulu Rock,” recorded in apartheid South Africa, with its single, “Mais où sont Passées Les Gazelles?” (“Where Have the Gazelles Gone?”), blew her somewhere that even her fans had never expected – the top of the charts in her native France.

Suddenly, the skinny, elfin outsider was being embraced in the homeland whose stuffy conventions she had fled in 1978 for Manhattan with her lover/manager and playmate, Michel Esteban.

His voice still tinged with wonder, Esteban recalls, “It was a hit, against all the odds. We started to get radio play. We spoke out in France against apartheid. Lizzy had not been known before in France, she was underground – now, she was a press story… the young French girl in New York, then South Africa, recording with black musicians… it was a real embrace of Lizzy by the press. Although “Zulu Rock” was not really rock, it was voted rock disc of the year.”

To Lizzy, who chose to end her days as an artist on the island of Corsica (she died of cancer in 2004) islands offered liberty and creative stimulation, the chance to, merge and meld her ideas with the local grooves among which they dwelled as transients. In the wilder realm of downtown Manhattan, they drank from native island rhythms like No Wave, New Wave, disco and salsa, recording “Press Color” (1979.) In Nassau, existing in an offshore bubble from the rest of the Caribbean, Lizzy cut “Mambo Nassau” (1981,) deracinated trans-national dance music, seasoned with Dakar, Kingston and SoHo.

Over the course of her five albums, Lizzy is consist in her inconsistency, darting like a firefly through the intriguing newfoundlands of “other” music, what might be perceived as “exotic”. But crucially, she felt so much a world citizen, a trans-national bard of displacement, that as her close friend, Linnaea Tillett (sister of Lizzy’s lover and muse, Seth Tillett,) says, “Lizzy was as alive in Soweto as she ever was in the downtown New York scene. Lizzy was just on fire in that period – as though she had found home in a way.”

They befriended each other in a time of social activism for Lizzy, who went on missions with Linnaea and her neo-anarchist comrades to places that in the late 1980’s crack frenzy, were, Linnaea says, “quite challenging, like Bensonhurst and Far Rockaway. Lizzy would say, “I’m with you!” She was a complex, political, engaged sort of person.”

Wanting to use her music to draw some attention to apartheid, even obliquely, Lizzy was also tapping in to a hot and little-heard dance music – the Shangaan disco and m’baqanga rhythms of South Africa. For her breakthrough track, “Mais où sont passées les Gazelles” (1984) , Lizzy’s vocal lopes with a warm, easy charm over a proven hit – the rhythm of the much-loved group Obed N’gobengi and the Kurhula Sisters’ “Ku Hluvukile Eka “Zete””. The original was written by the deep-voiced male lead singer, Ngobeni, with Peter Moticoe, a local musician and arranger who Esteban and Lizzy relied on in the making of her album.

Lizzy’s version is marked by the classic South African way of trading call and response between a gruff male and a crew of female singers. But she transforms the original, sprinkling it with her own laconic bohemian whimsy – passing the test of where clumsy appropriation merges into a jam, as a real exchange and an unexpected gas for all artists concerned.

Lizzy’s Soweto sojourn followed Malcolm McLaren’s mbaqanga/salsa/hiphop mix, “Duck Rock,” by a year after and was followed two years later by Paul Simon’s 1986 “Graceland.” Technically, they were all breaking the African National Congress (A.N.C.) cultural boycott, designed to put pressure on both the South African government and the world to stop the system that kept black Africans as second class citizens with no rights in their own country. But even within the A.N.C, it was understood that cultural exchange could be a grey area; awareness of the brilliance of South African music could only put a human face on the fight for equality. And Lizzy’s musical played a part here.

Among those who bought “Zulu Rock” – and still treasures the album – was music entrepreneur Donald “Jumbo” Vanrenen. He arrived in London from South Africa in the 1960s for political reasons. He helped found first Virgin Records, then his own pioneering African music label, Earthworks, whose 1985 compilation “The Indestructible Beat of Soweto” became an influential series.

“When Lizzy did her South Africa thing after Malcolm McLaren, it became the record to look our for,” he remembers, looking fondly at the sleeve of Lizzy with the Tyelimini girl singers and J.J. Chauka, in their cheery ra-ra skirts. “It was a pop record that supported African developments.”

“The original by Obed Ngobeni and the Kurhula Sisters is a classic of the Shangaan disco style, which is internationally popular in the mid 2010’s all over again as a high-speed electronic dance sound,” Vanrenen continues. “But the real 1980s sound captures a time when South Africa was fighting an underground war in Mozambique, Angola and Namibia and Mozambique. The Shangaan tribe is based around the border with Mozambique, so many Shangaan speakers were among the refugees flooding into South Africa.”

So the spring in Shangaan disco’s rhythm is really a survival mechanism. The early 1980s were a key time in South Africa’s struggle. Its pop music was a complex mosaic of different tribal styles, mostly aggressively danceable, none of which could be played on the radio, as it was not sung in English. Even though specifically political lyrics were impossible, the irresistible energy of the buoyant, bouncing, life-affirming music marked it as a resistance sound, anyway.

The music of South Africa seduced, subsumed and molded Lizzy. She sounds surer, more swinging, right from the first experimental tracks like “Mister Soweto,” that she recorded in Paris in the hopes of getting the Columbia deal (included in “Mambo Nassau.”) It was Lizzy’s first work with British producer Adam Kidron, who would soon become important in her life.

A great admirer of Lizzy’s, the influential head of Columbia, Alain Levy, first introduced Kidron to Lizzy, at her request; she was intrigued by Kidron’s flair at easing outsider bands like Scritti Pollitti into the mainstream, with authenticity. Lizzy and Adam’s was a battle of wills from the start. His insistence on getting Lizzy to sing in a more conventional, tuneful way, resulted in an emotional, ambitious, creative power struggle that made sparks fly – and was to deliver arguably her best vocals yet.

Commenting by email, Kidron bluntly remembers, “My first impression of Lizzy was that she couldn’t sing, but that she had that crazy Madonna, Neneh Cherry, Nina Hagen attitude thing going on, and a magical way with words - a marketer’s gift for getting to the essence of a feeling or idea. My job, given Lizzy’s limited vocal range – was to find a format to carry those words, and in that I was, over two albums, partially successful.”

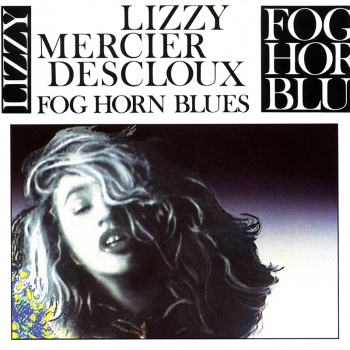

“First impressions be damned, as we became lovers almost instantly and dipped in and out of each other until the relative failure of Fog Horn Blues a few years later. Our relationship was like that, usually just a little bit shorter than the time it took to make a record, so perhaps a bit expeditious, quite volatile, and certainly filled with intrigue because though we were lovers of endless energy and passion, there were other lovers, which added intrigue.”

Esteban recalls how the success of the odd trio’s Paris demoes sent them on a trans- continental voyage.“ Alain Levy at Columbia gave us a blank cheque to explore Africa, inspire Lizzy, and come up with an album to record at Satbel Studios in Johannesburg. An extraordinary adventure. We followed the footsteps of Rimbaud, “ (the free-living young 19th century poet who was Lizzy’s hero,) through Sudan, Ethiopia, the East Coast. Lizzy wrote poetry and lyrics constantly.”

The trip was formative for Kidron, too, though, he claims, “Lizzy preferred whisky to Rimbaud.” He continues, “We travelled together to Egypt, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and South Africa, and that trip is one of the highlights of my life as there was a disorderly elegance to our discovery – Lizzy was a magnet for people and I am good at strategy so we went further and deeper into the places we visited than could be reasonably expected. We wanted to spend time together exploring - pyramids, the spiritual influences of Bob Marley and Rastafari, apartheid…..” he writes.

Like Lizzy’s other musical forays, ”Zulu Rock” finds her darting off to explore fairly recent enthusiasms, led by her gut instinct and feeling of affinity. But the reality of working in South Africa came as a shock, particularly to Lizzy and Michel.

“We had heard of apartheid, but when we confronted it directly – wow. Different cinemas for whites and blacks. We could not eat in a restaurant or go to a bar with the musicians. We had to have food brought to us. It was crazy,” says Esteban.

“At the record company offices, the secretaries were all very white with Lady Di coiffures, and they were certainly surprised if not shocked by us,” Esteban continues. “They couldn’t seem to understand why Paris or New York musicians might want to record in South Africa. When the musicians saw that Lizzy was nothing like the other white women around, they were a bit surprised too, even suspicious at first. But by the end, we all had good communication and a lot of fun together. And people said it was violent in Soweto, but we went anyway.”

Raised in the tradition of South African resistance, Kidron was less surprised by the brutality of the separatist laws. He too remembers their taboo township excursions fondly. “In the night we would break the pass-laws to go into Soweto to dance at the Pelican club (I think it was called,) where they spun Jive into Madonna, Human League and of course Michael Jackson. “

“How we came to record Zulu Rock is quite simple,” Kidron writes. “My dad was born in South Africa, and friends of his, especially Julius Levine, helped set up the recording. Jive was and is a funky mix of many quite traditional African musics and American R&B. We started by listening to a bunch of successful Soweto-Jive records, and then recorded similar backing-tracks with many of the musicians that had recorded the originals, replacing the vocal tracks and sometimes the melodies with Lizzy’s.”

Reflecting on the recording sessions, Esteban says, “The music of South Africa gave us an extraordinary feeling. We had a vision and a sound we wanted to hear for Lizzy’s collaboration there, but it was abstract. But finally, la mayonnaise c’est mise à prendre… everything started to blend. It was the most extraordinary experience of my career.”

Transported by the beat, Lizzy’s vocals have a new authority. On “Abysinnia” and “L’Eclipse,” she projects a different sense of lyricism and ease; on tracks like “Cri” and “Tous Pareils” the trademark random growls and yelps of Lizzy’s East Village days remain, but are now part of a broader range of textures at her command Lizzy is at her most tuneful when riding the Zulu rhythms of “Sun’s Jive.” Breathily weaving among male choruses and abstract animal sounds on “Confidente de La Nuit,” her own boulevardier personality gleams in her serene performance. She even has the confidence to sing in English on “Queen of Overdub Kisses,” one of various “hit” tracks on this record.

“Wakwazulu Kwezizulu Rock,” (three mixes of which appear here,) shows how Lizzy tuned in to the connection between the use of fiddle and accordion in the musics of both South Africa and New Orleans’ Cajun and zydeco. She delivers commands as if she was at a downhome country line dance, riding the stomping beat like a bronco. So exhilarated with the trans-cultural bond were Lizzy, Adam and Michel, that they planned to make the next leg of their recording escapades a dream cross-genre session in New Orleans. Preparations included weeks of meetings with the likes of Allen Toussaint. Ultimately, though, they were blocked by the South African government’s refusal to grant travel documents to the musicians.

“We were so disappointed not to be able to do what we wanted. We tried so long and it didn’t work out. Then we felt dry and realized we were out of ideas,” Michel says somberly.

But, against all odds as Esteban might say, the trio would reunite again two years later, when Kidron produced Lizzy’s penultimate album, ”One For The Soul,” in Rio de Janeiro. Yet again, Lizzy would find a new approach to her songs, this time with the help of master jazz trumpeter, Chet Baker, then in the twilight of his career… but more about that in the notes for Lizzy’s next album in this 5-CD set…as we trace Lizzy Mercier-Descloux’s quixotic and very individual journey…

++++++++++++++++++++++

Special thanks to Simon Clair and Adam Kidron for use of their works in progress on Lizzy Mercier-Descloux